Logical Fallacies in Edubabble

December, 2004

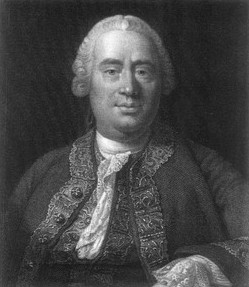

Let's begin with a portion of palaver from the great British philospher, Dave "Big Daddy" Hume. B. Diddy, as he was known on the streets, was fed to the backteeth with arguments having no empirical support--whose

persuasive force derived, instead, from rhetorical trickery.

"Principles

taken upon trust, consequences lamely deduced from them, want of coherence in

the parts, and of evidence in the whole, these are everywhere to be met in the

systems of the most eminent philosophers, and seem to have drawn disgrace upon

philosophy itself... Disputes are multiplied, as if everything was uncertain.

Amidst all this bustle, it is not reason

which carries the prize, but eloquence: and no man needs ever

despair of gaining proselytes to the most extravagant hypothesis,

who has art enough to represent it in any favourable colours.

The victory is not gained by the men at arms, who manage the pike and the

sword, but by the trumpeters, drummers, and musicians of the army."

[David Hume. A treatise of human nature.

1738]

Yup, B. Diddy about says it all...

After 35 years reading snappy stuff in education [35 years!! Seems like only yesterday we were greasing our hair, then sculpting

the oleaginous mass into a fair replica of waves breaking off

Critical Readers are invited to check this assertion.

Here, for example, are writings in the anti-progressive camp

("instructivists," as labeled by Chester

Finn and Dianne Ravitch)--the good guys. See if

you find many logical fallacies. [They're also just plain great resources.]

J.E. Stone. "Developmentalism:

An Obscure but Pervasive Restriction on Educational Improvement."

On-line at http://olam.ed.asu.edu/epaa/v4n8.html

Grossen, B. (1998). "What does it mean to be a research based

teaching profession?" On line at http://www.higherscores.org/

The case against teacher

certification.

See also Mike Podgursky's critiques of NCATE,

national boards, and teacher certification. At

http://www.missouri.edu/~econ4mp/Downloadable_Articles.htm

http://www.missouri.edu/~econ4mp/Downloadable_Papers

Eric Hanushek's critiques of the

assertion that class size and advanced teacher training make a difference in

student achievement http://edpro.stanford.edu/eah/eah.htm

Lance Izumi's and K. Gwynne Coburn's critique of constructivist curricula in

schools of education, Facing the classroom challenge: Teacher quality and teacher

training in California's schools of education, at http://www.pacificresearch.org/pub/sab/educat/facing_challenge/challenge.pdf

Pacific Research Institute at http://www.pacificresearch.org

Education Consumers at

http://www.education-consumers.com/ See articles by John Stone.

Fordham Foundation at http://www.edexcellence.net/

Hoover Institution at http://www-hoover.stanford.edu/research/k-12initiative/k12publications.html

National Council For Teacher

Quality. Alternative certification at http://www.nctq.org/

Education Leaders Council at http://www.educationleaders.org

No Excuses

Papers on effective instruction at http://www.usu.edu/teachall

Ellis et al., "Research synthesis on effective

teaching principles and the design of quality tools for educators."

On-line at http://idea.uoregon.edu/~ncite/documents/techrep/tech06.html

and http://idea.uoregon.edu/~ncite/documents/techrep/tech05.pdf

On-line at http://act.psy.cmu.edu/personal/ja/misapplied.html

Critiques of constructivist

math.

Mathematically Correct at http://www.mathematicallycorrect.com/

Heartland Institute: School Reform News at http://www.heartland.org/

Market Driven Schooling; e.g., vouchers "Understanding

market-based school reform."

Walberg, H.J., & Bast,

J.L. (1998). Heartland

Institute. Online at http://www.heartland.org

In marked contrast, here are samples [emphases mine] of

progressive blather bursting with illogic. No doubt their authors are at

this very moment minding their own business--perhaps giving the family cat a soothing ear bub or tummy

rub. Then again, maybe not.

But this is not the time to dwell on bubbings

and rubbings--feline or otherwise...

1. Our first sample is from a letter to the editor of Education

Week. It's the response made by Gerald Coles, a whole language

advocate, to an Education Week article that discussed the

effectiveness of direct instruction of reading skills.

"Is

this 'war' really about skills and how to teach them? On the surface it is, but

adequately understanding the conflict requires addressing deeper

issues ingrained in the arguments about teaching method.

One concerns broad goals for children's development.

Accompanying the call for the direct instruction of skills is a managerial,

minimally democratic, predetermined,

do-as-you're-told-because-it-will-be-good-for-you form of instruction.

Outcomes are narrowly instrumental, focusing on test

scores of skills, word identification, and delimited conceptions

of reading comprehension. It is a scripted pedagogy for producing

compliant, conformist, competive students and adults."

(Gerald Coles. "No end to the reading wars." Education

Week,

[Mr. Coles's flamboyant

rhetoric--which no doubt exerts strong pressure on the glands of his

many-headed whole language followers--is an example of the fallacy

of prejudicial language. He's trying to defend whole language

against explicit and systematic reading instruction. Unfortunately (for

persons who prefer evidence as a side dish to the main course of infected

flop), Mr. Coles's argument provides NO data that

direct instruction does not work as well as whole language, or that direct

instruction on has any of the adverse effects Mr. Coles recites.

Instead, typical of self-styled progressives, Mr. Coles uses a

string of negative terms to demonize direct instruction. The bogus implication

is that any reader with children's interests at heart will reject direct

instruction and embrace whole language. If direct instruction is minimally

democratic, for example, then whole language must be maximally democratic.

However, Mr. Coles gives no evidence that supports his caricature of direct

instruction or the implied valorization of whole language.

The argument is also close to ad hominem,

because Mr. Coles not only tars direct instruction but also persons

who advocate direct instruction. For example, in the beginning of the excerpt,

he asserts that the reading "wars" are not merely about evidence and

instruction; the wars reflect "deeper" issues--namely the values and

objectives of advocates. The implication is that only those persons who are

anti-democratic, managerial, and want to tell children exactly what to do would

be for direct instruction.]

2. This sample is part of an argument in favor of

constructivist teaching. I believe it won a prize for Most Nonsense

Packed Into One Line.

"We

cannot understand an individual's cognitive structure without observing it

interacting in a context, within a culture." (Fosnot,

1996, p. 24)

[The fallacy here is a "category mistake"--in

this case treating an intellectual fiction (cognitive structure) as if it were

a physical

object. "Cognitive structure" is NOT an object. It can't

be

observed because it's not an it.

By treating the loose aggregation of beliefs, skills, and ways of doing things

(that is called "cognitive structure") as if it were object, and then

by saying that this cognitive structure can only be observed as it interacts

in a context, the author lays the groundwork for constructivist methods of

loose assessment and instruction.]

In other words, ed professors, teachers, and ed students

(well-trained in airy "edspeak") can talk

at length and with great confidence about children's cognitive structures--how

these fictitious entities are developed via constructivist

"practices" ("My children's cognitive structures are so much

more open and complex since we began using inquiry methods.")--without having any idea at all what they are talking about.

3. This sample of constructivst argumentation sets up a false

dilemma. By vilifying one curriculum (behavioral), the

writers try to persuade readers to accept the other (the writers')

constructivist curriculum.

"We

see two major assumptions of the behaviorist approach that contrast with the

assumptions of the constructivist approach. The first broad assumption of the

behaviorist approach is that environmental stimuli shape and control individual

behavior responses. This assumption reflects the view that the child's

interests and purposes are irrelevant and leads to teacher-centered power

assertion in relation to children. This is in contrast to

the constuctivist view that the individual must

actively construct knowledge, including stimuli and responses. The reader will

recognize the practical implications of this behaviorist assumption as

contradictory to constructivist cooperation in relation to children."

(DeVries and Zan, 1994: p.

267)

[This argument commits the fallacy of false

dilemma. The argument is that there are only two alternatives:

(1) If a person believes the environment shapes behavior, then the person will

view children's interests and purposes as irrelevant and will use his or her

power to control children. But

(2) If a person believes children "construct" stimuli

and responses, then the person will view children's interests and purposes as

relevant, and will cooperate with children, rather than dominate them.

This false dilemma is supposed

to get readers to reject "behaviorism" and embrace "the

constructivist" classroom. The flaw is--there

is no dilemma, and so a person does not have to choose one or the

other position.

The above passage also verges on ad

hominem; it implies that any

"behaviorist" is a coercive teacher, and that is a bad thing;

therefore, we should not pay attention to what behaviorists have to say. In

addition, there is no

evidence that any of the writers' propositions are true.

The writers apparently hope readers will be swayed by provocative words--which is

the fallacy of prejudicial language.

4. This sample suffers from an intellectual disorder that

might be called "acute drivel syndrome." The

writing is so stupendously infected with reification, tautology, bad grammar,

and over-statement, that inattentive readers might

assume the writing is profound when in fact the argument is grotesque

nonsense.

"From

this perspective, learning is a constructive building process of meaning-making

that results in reflective abstractions, producing symbols within a

medium." (Fosnot, 1996,

p. 27). "Reflective abstraction is the driving force of

learning." (Fosnot,

1996, p. 29).

[First, notice the circularity in the

line, "learning is a constructive building process of meaning-making that

results in reflective abstractions, producing symbols

within a medium," followed by "Reflective abstraction is the

driving force of learning." One moment reflective abstraction is the

result

of learning (meaning construction). The next moment reflective

abstraction is the driving force behind learning.

Well, which is it?

Second, the excerpt contains examples of reification:

learning is not said to be like a building process;

it is

a building process. Likewise, reflection is said to be a driving force.

But what is reflection? Reflection means talking to yourself.

What kind of force is that? How can talking to yourself drive learning?

Do you talk first and then learn? Nonsense! [But in the field of

education, this sort of piffle is commonly seen as wisdom.

Third, notice how the author connects phrases into what comes

off sounding profound, but means nothing. What, after all, is

"meaning-making"? Is it something persons do alongside

acting? "I'm writing a paper. Occasionally I stop to make

meaning." And the phrase "producing symbols in a medium"

is simply incomprehensible. What medium? A dish

of agar?]

5. This sample tries to make the case, "It's right

for us; therefore, it's right for everyone."

"Reform...is

not easy, but how we conceptualize things makes a difference. The viable

alternative we have been exploring involves reconceptualizing the whole of education as

inquiry. For

us and the teachers with whom we work, education-as-inquiry

represents a real shift in how we think about

education...We want to see reading as inquiry, writing as

inquiry, classroom discipline as inquiry, and both teaching and learning as

inquiry. Instead of organizing curriculum around disciplines, we

want to organize curriculum around the personal and social inquiry

questions of learners...Inquiry as we see it is about

unpacking issues for purposes of creating a more just, a more equitable, a more

thoughtful world...Theoretically, education-as-inquiry finds its roots in whole

language, sociopsycholinguistic, or, these days what we

prefer to call socio-semiotic theory or what others call cultural

studies." (Harste & Leland, 1998. p. 192-3)

[This excerpt has several fallacies. One is the fallacy of hasty

generalization, or converse accident--which

means generalizing from a unique circumstance to other settings.

The writers admit that their education-as-inquiry perspective is "how we

think about education" and that it is about "unpacking issues for

purposes of creating a more just, a more equitable, a more thoughtful

world." Perhaps this works well for them in their special

circumstances. However, they propose to go well beyond their

experiences. They wish to prescribe a conception of

education, aims of education, and a curriculum for everyone.

(The Right-thinking Citizen says, "Thanks, but No Thanks, Comrade.")

A second fallacy is fallacy is prejudicial language.

The writers are trying to make a case for their education-as-inquiry conception

and curriculum. But do they offer any good reasons for these innovations? All

they offer is gaudy visions of a just, thoughtful and equitable world. These

words appeal to many readers' sentiments and hopes. But these words are hardly

a good reason for accepting the authors' proposed innovations. After all, the

world's graveyards are filled with millions of individuals who died for someone

else's notion of justice--just as schools and prisons are

filled with persons who had been subjected to ed

professors' nutty notions of what constitutes good teaching.

6. This sample contains wonderful examples of circular

reasoning. Caution. If you

are prone to vertigo, don't read it. [I had vertigo once, for about 10

seconds. Now THAT is scary!]

"...when

parents and teachers plan children's environment and activities carefully so

that literacy

is an integral part of everything they do, then literacy learning

becomes a natural and meaningful part of children's

everyday lives. When you create this kind of environment, there is no need to

set aside time to teach formal lessons to children about reading and writing.

Children will learn about written language because it is a part of their

life." (Schickendanz, 1986. p. 125)

Feel dizzy? The argument goes round and round without saying

much. That's because the entire argument is a big circle.

The first sentence asserts a proposition about the relationship between the

literature richness of a child's environment (independent variable) and the

extent to which literacy learning becomes a natural and meaningful part of

everyday life (dependent variable). On the surface, this seems plausible. But

that's because the proposition is asserting nothing more than "X is

X." Read the sentence carefully. The phrase "literacy is

an integral part of everything they do" means the same thing

as "literacy learning becomes a natural and meaningful part of children's

everyday lives." Therefore, of course the proposition seems intuitively

reasonable; because an "integral part of everything" IS "a

natural and meaningful part."

The second circularity is in the second to last sentence, which

asserts that when a child has a literature rich environment (independent

variable), there is no need for formal reading instruction (dependent

variable). The next sentence ("Children will learn about written language

because it is a part of their life.") appears to explain

why this might be so--i.e., why a literature rich environment makes formal

instruction unnecessary. But instead, of asserting that some new

sort of thing happens in a literature rich environment that

does the teaching, the next sentence ("Children will learn

about written language because it is a part of their life.") merely

repeats the gist of the first sentence, but in reverse order.

[Give me a minute and I'll write something long-winded!]

So, the argument boils down to this. (1) A literature rich

environment teaches children to read, because... (2) Children learn to read in

a literature rich environment.

Wow! How informative! What a sane person wants to know is, HOW does a literature rich environment teach children to

read without formal instruction? Unfortunately, the authors don't

have anything to say about this. (But we didn't think they would.)

Well, that's all we have time for--and no doubt I exhausted your

tolerance long ago.

But what accounts for arguments that are so illogical?

In my humble op, it's that progressivist

writers really DON'T know what they are talking about.

In fact, they are often talking about nothing at all.

Therefore, anything they have to say about nothing has to come out pretty

drippy.

The other reason is that they have no credible data to support

their teaching methods and no credible data to support their criticisms of

their opponents who offer effective (more traditional) instruction. Therefore, they

have to make something up--something that sounds good--but is

(and can only be) all rot.

DeVries, R., & Zan, B. (1994). Moral classrooms, moral children.

Fosnot, C.T. (Ed.)

(1996). Constructivism :

theory, perspectives, and practice.

Harste, J.C.,

& Leland, C.H. (1998). No quick fix: Education as inquiry. Reading Research and

Instruction, 37, 3, 191-205. Kauffman, J.M.,

& Hallahan, D.P. (1995).

Schickendanz, J.A. (1986). More

than the ABC's: The early stages of reading and writing.